Comfort in good times and bad

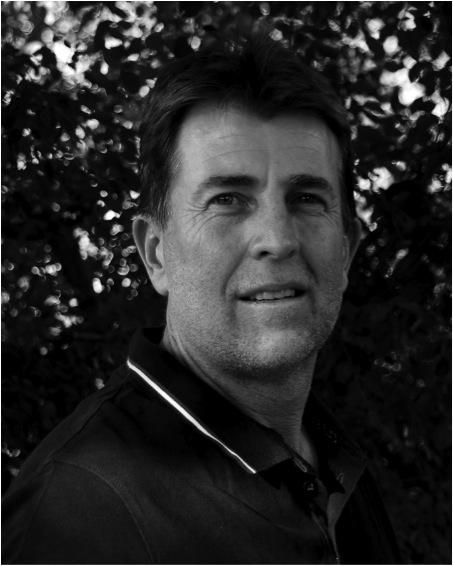

The Zimbabwean poet Togara Muzanenhamo (1975) is one of the guests at the Poetry International Festival in Rotterdam. Sander de Vaan spoke to Togara shortly before his arrival in the Netherlands.

(from meander magazine.net. Translated using Google translate)

How would you like to present youself to the Dutch public?

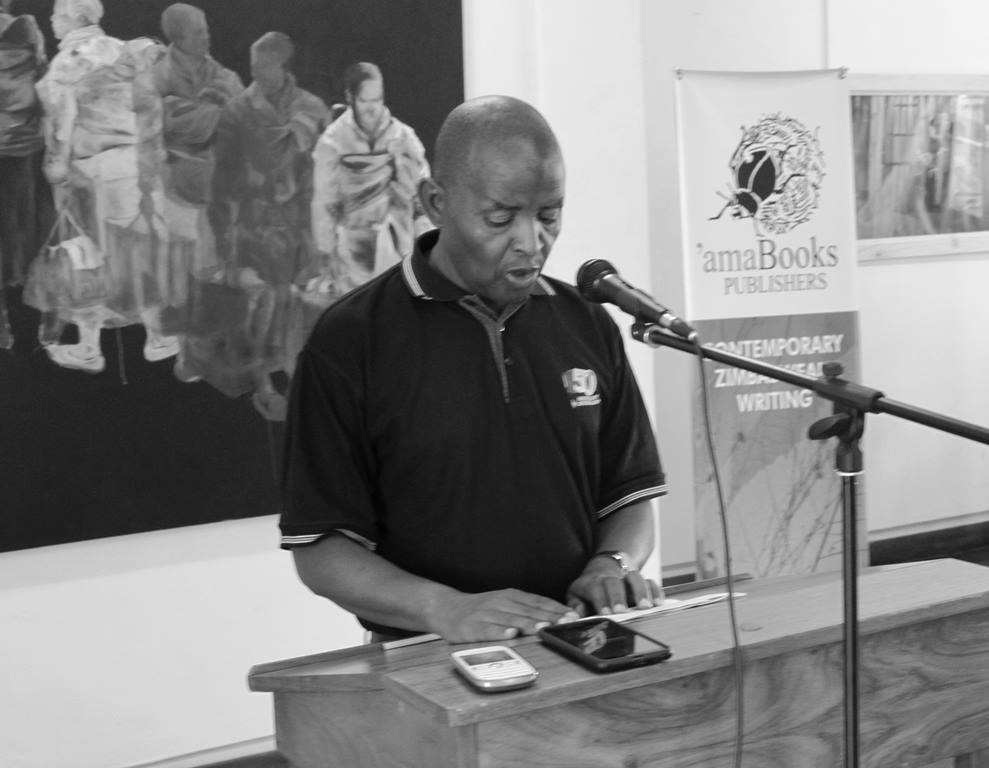

I was born in the Zambian city of Lusaka and raised on a farm about 50 kilometers from the city of Harare in Zimbabwe (the homeland of my parents). After school I started studying Business Administration at The Hague and Paris. And in The Hague, I started writing poetry. After my studies, I returned to Zimbabwe where I first went to work as a journalist and then as a screenwriter. In 2001 I moved to England to pursue a Master's in creative writing headed by Simon Armitage and Carol Ann Duffy. Five years later, my first book, Spirit Brides (Carcanet Press), which was shortlisted for the Jerwood Aldeburgh First Collection Prize. In 2012 I was invited to the gala of the Southbank Centre's Poetry Parnassus in London, where I recited poems accompanied by Seamus Heaney, Kay Ryan, Wole Soyinka and others. My second collection, Gumiguru, appeared in 2014 and shortly thereafter followed Textures, published by amaBooks in Zimbabwe. Textures was written in collaboration with the Zimbabwean poet John Eppel.

I was born in the Zambian city of Lusaka and raised on a farm about 50 kilometers from the city of Harare in Zimbabwe (the homeland of my parents). After school I started studying Business Administration at The Hague and Paris. And in The Hague, I started writing poetry. After my studies, I returned to Zimbabwe where I first went to work as a journalist and then as a screenwriter. In 2001 I moved to England to pursue a Master's in creative writing headed by Simon Armitage and Carol Ann Duffy. Five years later, my first book, Spirit Brides (Carcanet Press), which was shortlisted for the Jerwood Aldeburgh First Collection Prize. In 2012 I was invited to the gala of the Southbank Centre's Poetry Parnassus in London, where I recited poems accompanied by Seamus Heaney, Kay Ryan, Wole Soyinka and others. My second collection, Gumiguru, appeared in 2014 and shortly thereafter followed Textures, published by amaBooks in Zimbabwe. Textures was written in collaboration with the Zimbabwean poet John Eppel.

Zimbabwean poetry is not well known in Europe.Where are you situated in the contemporary poetry of your country?

It is true that the poetry from my homeland is not well known, but still has a number of poets who have received recognition in Europe and other continents. Take for example Julius Chingono, who appeared several years ago at Poetry International. And poets like Chirikure Chirikure, Chenjerai Hove, Tsitsi Jaji, Dambudzo Mara Chera, Charles Mungoshi, Blessing Musariri and Musaemura Zimunya are also reasonably known abroad. About my own position, I can not say too much, because my work has only been available since last year in Zimbabwe.

It is true that the poetry from my homeland is not well known, but still has a number of poets who have received recognition in Europe and other continents. Take for example Julius Chingono, who appeared several years ago at Poetry International. And poets like Chirikure Chirikure, Chenjerai Hove, Tsitsi Jaji, Dambudzo Mara Chera, Charles Mungoshi, Blessing Musariri and Musaemura Zimunya are also reasonably known abroad. About my own position, I can not say too much, because my work has only been available since last year in Zimbabwe.

What is poetry for you?

For most of my adult life poetry has been an integral part of my thinking. When I began to write poetry, I wanted to be no 'poet'. It was mainly my fascination with language for a word, the magic of the language rhythm, the power of an idea or a thought. And that is true to this day true: the more poetry I read, the more intrigued I become about her function.

For most of my adult life poetry has been an integral part of my thinking. When I began to write poetry, I wanted to be no 'poet'. It was mainly my fascination with language for a word, the magic of the language rhythm, the power of an idea or a thought. And that is true to this day true: the more poetry I read, the more intrigued I become about her function.

Which poets have influenced you?

The first poet that really touched me was Seamus Heaney. He gave his poems an honesty and depth which particularly appeal to me and there are always new things to discover, no matter how many times I read or listen to his poems.

Furthermore, I admire the poet Charles Simic, because he has been able to change my perspective on the physical and emotional worlds of poetry. Les Murray was a great teacher about the landscapes and rural life with which I am familiar. And Musaemura Zimunya has very beautiful poems written about my country. Four books given to me in my early days as a poet have especially touched me: The Wild Iris (Louise Glück), Hotel Insomnia (Charles Simic), Trembling Hearts in the Bodies of Dogs (Selima Hill), and Spirit Level (Seamus Heaney).

The first poet that really touched me was Seamus Heaney. He gave his poems an honesty and depth which particularly appeal to me and there are always new things to discover, no matter how many times I read or listen to his poems.

Furthermore, I admire the poet Charles Simic, because he has been able to change my perspective on the physical and emotional worlds of poetry. Les Murray was a great teacher about the landscapes and rural life with which I am familiar. And Musaemura Zimunya has very beautiful poems written about my country. Four books given to me in my early days as a poet have especially touched me: The Wild Iris (Louise Glück), Hotel Insomnia (Charles Simic), Trembling Hearts in the Bodies of Dogs (Selima Hill), and Spirit Level (Seamus Heaney).

What makes you think the difference between a good poem and an extraordinary poem?

When I started to read poems, something interesting happened: the silence of the written word produced music in my mind, a music orchestrated with images that sprang from words and feelings - words, images and thoughts that came together in a sort of honesty or truth. A good poem arouses certain elements of that music, but an extraordinary poem pulls you into the words and feelings, so that you are part of the art.

I experienced this for the first time when I read 'Postscript' by Seamus Heaney. Suddenly I realized I was part of the words and the music.

When I started to read poems, something interesting happened: the silence of the written word produced music in my mind, a music orchestrated with images that sprang from words and feelings - words, images and thoughts that came together in a sort of honesty or truth. A good poem arouses certain elements of that music, but an extraordinary poem pulls you into the words and feelings, so that you are part of the art.

I experienced this for the first time when I read 'Postscript' by Seamus Heaney. Suddenly I realized I was part of the words and the music.

How do you usually start a new poem?

A poem can occur in different ways. Normally, it starts with an idea that sits in my head singing for a few days, weeks or even months. This happens especially when I'm not familiar with a subject and I need to do research for a text. As I sit pondering how to reforge a thought into a poem, I read as much as possible about the subject and create a first draft. Then I create a whole new set of sketches and trial versions until I am satisfied with the final text.

But I begin a poem by regularly - usually at night - sitting at my desk and simply writing down everything that comes to me. Then it is kind of blindly walking around, when I'm never sure of the result and there is no specific goal. Sometimes I write three to five sketches, which I then store, and later, when I have time or I am looking for material for a poem, again take in hand.

A poem can occur in different ways. Normally, it starts with an idea that sits in my head singing for a few days, weeks or even months. This happens especially when I'm not familiar with a subject and I need to do research for a text. As I sit pondering how to reforge a thought into a poem, I read as much as possible about the subject and create a first draft. Then I create a whole new set of sketches and trial versions until I am satisfied with the final text.

But I begin a poem by regularly - usually at night - sitting at my desk and simply writing down everything that comes to me. Then it is kind of blindly walking around, when I'm never sure of the result and there is no specific goal. Sometimes I write three to five sketches, which I then store, and later, when I have time or I am looking for material for a poem, again take in hand.

I was charmed by your poem "Six francs seventy-five." Poetry can also provide comfort?

I have always benefited greatly from reading poetry. Both in good times and in bad times. Many people resort to poetry at sad moments or in doubt. And listening to poetry also has a calming effect. Poems can cause emotional healing and growth.

I have always benefited greatly from reading poetry. Both in good times and in bad times. Many people resort to poetry at sad moments or in doubt. And listening to poetry also has a calming effect. Poems can cause emotional healing and growth.

SIX FRANCS SEVENTY-FIVE

Each night we bought red wine from a small supermarket

Not too far from the Seine, where an overweight deaf counter

Smiled whenever we Walked in. At the counter he read our lips

As we bought the cheapest wine we could find - never any change

Ashes each time we paid, we paid the exact amount of coins you

Counted, one by one, into his open palm: six francs seventy-five.

Not too far from the Seine, where an overweight deaf counter

Smiled whenever we Walked in. At the counter he read our lips

As we bought the cheapest wine we could find - never any change

Ashes each time we paid, we paid the exact amount of coins you

Counted, one by one, into his open palm: six francs seventy-five.

Late in the evening you'd count up another six seventy-five

And we'd walk through the narrow streets back to the supermarket -

Fumbling through rich Parisians On Their Way to dinner; and you,

Who loved the city for our anonymity, Became fond of the young counter

Who Seemed alone and estranged and liked us too for the change

We brought to his long nights, When He read our hearts and lips.

And we'd walk through the narrow streets back to the supermarket -

Fumbling through rich Parisians On Their Way to dinner; and you,

Who loved the city for our anonymity, Became fond of the young counter

Who Seemed alone and estranged and liked us too for the change

We brought to his long nights, When He read our hearts and lips.

Remember, when, we figured out what he asked behind his mute lips,

"Why come twice, why not save yourself the walk and buy four or five

Bottles in the early evening? "We laughed, as nothing would change

The way we bought or the walks we firing, hand in hand, to the supermarket.

The following evening, as we paid, we looked into the eyes of the deaf counter

And Said, "It's our habit" and left it at That; and he smiled, more so at you.

"Why come twice, why not save yourself the walk and buy four or five

Bottles in the early evening? "We laughed, as nothing would change

The way we bought or the walks we firing, hand in hand, to the supermarket.

The following evening, as we paid, we looked into the eyes of the deaf counter

And Said, "It's our habit" and left it at That; and he smiled, more so at you.

From That Night on - every night, this game with him and you;

He'd lift his finger and wait for the silent words to form on our lips

And we'd say, "it's our habit"; and he'd laugh - the deaf counter -

As we played our game and all we needed was six francs seventy-five

On those evenings near the banks of the Seine, in That small supermarket -

Always paying the exact amount, never receiving any change.

He'd lift his finger and wait for the silent words to form on our lips

And we'd say, "it's our habit"; and he'd laugh - the deaf counter -

As we played our game and all we needed was six francs seventy-five

On those evenings near the banks of the Seine, in That small supermarket -

Always paying the exact amount, never receiving any change.

Then you left and went away, and so heartfelt was the change -

Each night I cried, and it's safe to say That he too sorely missed you.

In the evenings I still walk the narrow streets to the supermarket -

Remembering our walks in expensive coats, the jokes and your pale lips,

The way you kept the coins in a velvet pouch - the six seventy-five

That you'd always count into the soft, open palm of the deaf counter.

Each night I cried, and it's safe to say That he too sorely missed you.

In the evenings I still walk the narrow streets to the supermarket -

Remembering our walks in expensive coats, the jokes and your pale lips,

The way you kept the coins in a velvet pouch - the six seventy-five

That you'd always count into the soft, open palm of the deaf counter.

The night before I went away, I looked into the eyes of the deaf counter

And told him I was leaving the next day, his round face changed,

Something sad swelled in his young eyes as I Placed the six seventy-five

Into his palm; he then signed to the sky, asking if I was on my way to you -

But no words this time, I could say nothing, no words of you from my lips.

I packed the bottles of wine and slowly Began to exit the supermarket.

And told him I was leaving the next day, his round face changed,

Something sad swelled in his young eyes as I Placed the six seventy-five

Into his palm; he then signed to the sky, asking if I was on my way to you -

But no words this time, I could say nothing, no words of you from my lips.

I packed the bottles of wine and slowly Began to exit the supermarket.

The deaf counter ran to me, tapped me on the shoulder as I thought of you,

With no change to his eyes, he shook my hand and silently Said with his lips,

"It's our habit, and exactly six seventy-five." I smiled and left the supermarket.

With no change to his eyes, he shook my hand and silently Said with his lips,

"It's our habit, and exactly six seventy-five." I smiled and left the supermarket.

From: Spirit Brides

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment